Editor’s Note: The following is not legal advice. If you need legal advice, please consult with a legal advisor. post-pandemic clauses

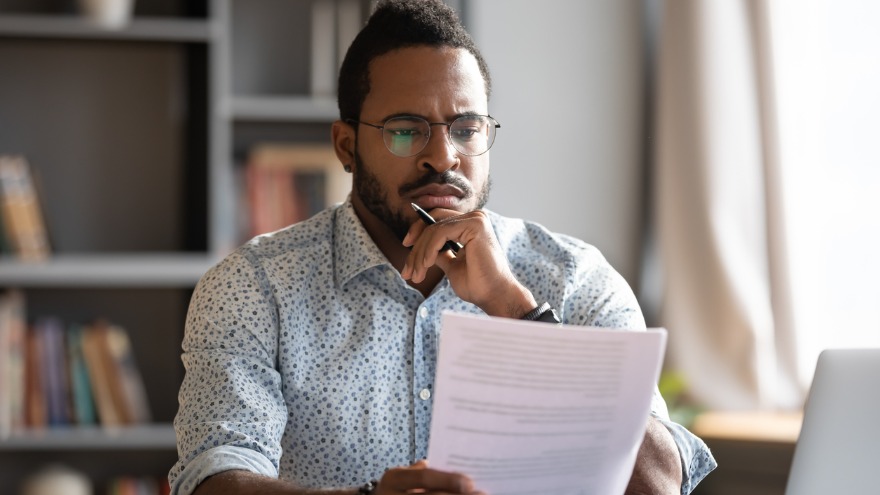

“The answer will always be ‘it depends,’” Ty Sheaks, attorney, author and faculty legal advisor to International Association of Venue Managers, began the latest Smart Meetings webinar, Post-Pandemic Contract Clauses You Need to Know. As unsavory as that answer is, in the world of federal, state, county and city guidelines and their differences in rules, this is the way it is.

Clauses Galore

“Your force majeure clause is [usually] going to have one or two versions. There’s the long form and the short form,” Sheaks says. In a long form, “there’s a big, long definition in there and a big block that lists out everything and anything people can think of that could possibly be considered force majeure. Your tornadoes, earthquakes, hurricanes and fires.”

More: The Most Prepared States for Natural Disasters

Short form usually just has catch-all language; broad descriptions of reasons the activities covered by the contract make them impossible, impractical or illegal to perform.

If you don’t have a force majeure clause in your contract, you can add it through a rider or addendum to the contract already in place. Sheaks advises against being too specific. “If you’ve got a force majeure clause you revise, and you just add Covid-19 and then the next variant of Covid-20 comes along, legally you wouldn’t be covered,” he says.

Other keywords that Sheaks has included in the new or revised definition of force majeure include “governmental actions,” “emergency declaration,” and “any law or action taken by a government or public authority.” That’s to cover restrictions and edicts issued by entities like the CDC; make sure the language is broad enough to cover every contingency.

When you’re dealing with larger hospitality properties owned by one of the big players—a Marriott, for example—its team of in-house lawyers may not be as open to renegotiating, in Sheaks’ experience. A franchisee, he adds, may be more willing to deal with you or make changes to the contract.

If your force majeure list doesn’t include the new things, such as a viral outbreak or pandemic, that’s the stuff you need negotiate, Sheaks says.

Another key item Sheaks says to look for is the “choice of law” clause. What that means is, what state’s law will apply if you’re unable to hold up your end of the contract? If you’re a meeting planner booking a meeting for a different state, do you want your home state or the hosted meeting’s state law to apply? “Choice of law will govern whether your force majeure clause is going to be valid or not,” Sheaks says.

Pay attention to notice requirements, as well. This section of the contract spells out the medium through which you’re to notify the other party if necessary—typically, a specific e-mail or postal address. “This was a huge issue for all the business interruption claims [made to insurance carriers] and why a bunch of those got denied initially,” Sheaks notes. “They weren’t notified properly.”

The last question to ask is, is it better to suspend or terminate the entire contract? Sheaks says to keep in mind that some states terminate clauses only.

Common Law Principles

“Frustration of contract,” a common law principle, is also available in most states. There are usually three main requirements, depending on state law.

First, the triggering event must render the contract impossible to fulfill or cause fulfillment to be radically different from what was contemplated when the contract was entered into.

“A lot of the times when [the venue lawyers] say, ‘No, it doesn’t count,’ it’s because people were scared [they] were going to lose money,” Sheaks says. This isn’t reason enough to bail, even for common law.

A second major requirement is the event that caused the change cannot be due to either party.

The third requirement is not having a force majeure clause or contract law that spells out what would happen if the show can’t go on.

Other Contractual Considerations

When you’re looking at contracts to redo or if the contract for an event you’ve pushed is now back on, here are things Sheaks says to make sure to take a close look at.

The limitation of liability clause is a huge one, he says. “This refers to who’s going to be responsible. Is it you, or are you passing the responsibility to another party as part of the contract?” he says. “Depending on how this clause is written, it may be you.”

If you’re booking bigger events or concerts and venues, make sure the contract includes terms and conditions from third parties. If Ticketmaster or SeatGeek is handling your ticketing, for example, they may have their own terms and conditions. “You can simply write a little addendum to your contract stipulating that all third-party terms and conditions are incorporated as part of the contract,” Sheaks says.

Backlogged Lawsuits Require Alternative Measures

The pandemic has clogged the courts with lawsuits, and what would once take a couple of years to find its way on the court docket may now take five years. For this reason, Sheaks suggests an alternative. “Think about dispute resolution clauses or maybe an arbitration. Maybe an early mediation requirement before a lawsuit can be filed,” he says.

Sheaks likes to include those in the draft contract for his own clients, as it’s sometimes easier to work it out just between the affected parties. “If we can’t [work it out], then we do an early mediation with an agreed mediator; then, if [that doesn’t result in an agreement], you can either file a lawsuit or go to arbitration.

Arbitration is usually more confidential. “Anytime you file a lawsuit, that’s going to be on the public record,” Sheaks says. In state and even a federal court, you run the risk of airing dirty laundry in public. “Are you willing to deal with that blowback?”

Who Makes the Rules?

Finally, Sheaks also shed light on who takes priority when it comes to guidelines.

“I would arguably say it’s your federal regulations, which constantly refer to the CDC; if the CDC says, ‘yay’ or ‘nay,’ that will typically trump your lower-level things,” he says. “But not in all cases.” Sheaks gave the example of Texas, where the state said venues could be open at 50 percent capacity, yet Dallas County said it wouldn’t follow the state guidelines.

Sheaks’ advice: “If you’re in Dallas County, better follow Dallas County. I mean, you’ve heard about those people that went to jail for trying to reopen their businesses. The safest bet is to figure out all the different regulations that apply, try to comply with them all, and then if there’s a difference between them, work that out with your event host. Then you guys can collectively make a decision.”