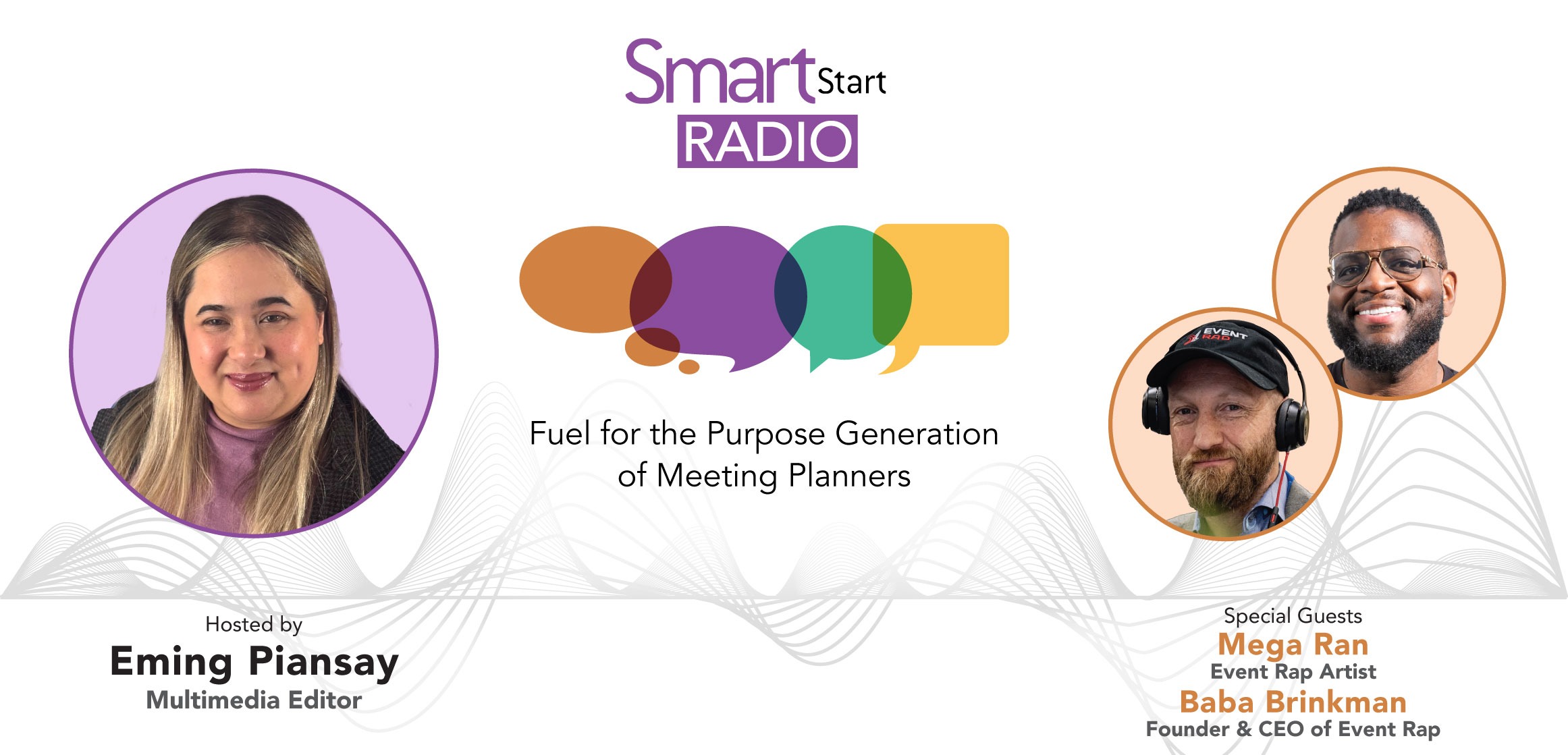

In this episode of Smart Start Radio, host Eming Piansay steps into the world of Event Rap, the creative powerhouse blending hip hop, storytelling and live performance to transform how audiences experience conferences. Founder Baba Brinkman breaks down how his background in literature and “peer-reviewed rap” evolved into a full-scale service that turns keynote themes into high-energy musical moments. From custom anthems to rapid-fire “rap-up” recaps, he explains why hip hop is the ideal medium for engagement, clarity and connection.

Eming then sits down with Grammy-nominated artist Mega Ran, the headline performer who brought Event Rap’s signature style to the Emergency Nurses Association conference in New Orleans. He shares his process—how he listens, takes notes, shapes hooks everyone can sing and delivers performances that resonate with audiences who may not think of themselves as hip hop fans.

And yes — this episode marks the debut of Smart Start Radio’s brand-new theme song, created exclusively by Event Rap and performed by artist Jam Young. You can explore his full bio and work at eventrap.com/artist/jam-young. The new track is bold, original and signals a fresh era for the show. The full song plays at the end of the episode, so stay to the very last beat.

Eming Piansay

Welcome back to Smart Start Radio. I’m your host, Eming Piansay, coming to you from Smart Meetings Studio. This episode is especially exciting because it brings together three of my favorite things—music, hip hop and live events.

A couple of months ago, I attended the Emergency Nurses Association meeting in New Orleans and watched a keynote unlike anything I had seen before. An artist from Event Rap listened to the keynote and performed it back to the audience in a hip hop format. I’ll share a sample of that later in the episode.

You may also notice that our theme music sounds different today. Event Rap created a brand-new intro for the show, and I’ll play the full track at the end of the episode. For now, we’re starting with my conversation with Event Rap founder Baba Brinkman.

EP

You founded Event Rap. You saw the vision early and understood how rap could elevate events, educate audiences and give artists a new way to earn. Walk me through how that idea formed and how you arrived where you are now.

Baba Brinkman

I’m originally from Vancouver, and I grew up as both a hip hop fan and an English literature nerd. I studied comparative literature and had an “aha” moment in college — Chaucer, Shakespeare, Blake, Nas, Jay-Z and Eminem were all doing the same thing: rhyming storytelling for their time. I wrote my honors thesis comparing The Canterbury Tales to hip hop culture and even created a modern rap adaptation of Chaucer. That became my touring show for several years.

Teachers and students started using my rap version of The Canterbury Tales to understand the material, which made me realize that rap is a powerful way to deliver ideas, even complicated or archaic ones. That was the early seed of what would become Event Rap — the idea that you can take something complex, make a rap about it and suddenly it becomes engaging and memorable.

EP

How did that turn into what you do today?

BB

After touring the Chaucer rap, a biologist approached me about turning Darwin’s The Origin of Species into a rap show. That became my first “peer-reviewed rap.” He fact-checked the lyrics before I performed them. From there, I spent about a decade doing science rap. The model was always the same: work with an expert, learn the material, mirror their language and turn it into a performance.

That process translates perfectly to events. For ENA, the Emergency Nurses Association gave us background materials, and Mega Ran wrote the anthem in collaboration with them. It’s the same peer-review model — just applied to corporate meetings, conferences and association events.

EP

Event Rap now offers custom anthems, freestyle segments and rap-up recaps written on site. How did that structure come together?

BB

It evolved through years of performing at conferences. Hip hop has a culture of speed — writing a verse in an hour, freestyling on command and performing without rehearsal. Those skills turn out to be extremely useful for events, where themes and moments are unfolding in real time.

We shaped that into three service models:

- Freestyle, created instantly with no preparation

- Rap-up, written during the event and performed at the end

- Custom rap or anthem, created with the client in advance

Each one fills a different need in the event flow. An anthem captures mission and values. A rap-up reflects what happened that day. A freestyle energizes a room the moment it begins. Planners can mix and match based on their goals.

EP

You mentioned hip hop’s built-in flexibility — the speed, the improvisation, the ability to shape something in real time. How does that connect to the way you build material for events?

BB

Hip hop has a long tradition of writing under pressure. In underground circles, someone will book a studio session, look at another artist and say, “Jump on this track. Give me sixteen bars.” You don’t get a week to prepare. You sit down, write and deliver.

That culture makes rappers uniquely qualified for what events demand — fast thinking, high adaptability and the ability to turn a lot of information into something cohesive and entertaining in a short time. At an event, themes are unfolding live. People are presenting, panels are happening and moments are emerging that you can’t predict. Rap responds to that rhythm naturally.

Event Rap artists work in three ways:

• They freestyle on the spot.

• They write rap-up recaps during the event and perform them immediately.

• They collaborate with clients in advance to create anthems that represent the spirit of the group.

Each one fits a different moment in the event. The anthem sets the tone. The freestyle energizes people. The rap-up reinforces what was learned and sends everyone out with a shared sense of connection.

EP

That makes a lot of sense. You’ve talked before about how your background in medieval literature influenced your approach. Can you expand on that?

BB

In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, artists worked on commission. The Sistine Chapel ceiling exists because someone said, “We need a ceiling painted.” Commissioned art wasn’t considered lesser — it was a respected way of creating work with purpose.

Rap has relied on album sales and live shows, but I think the patronage model has real value for hip hop. When someone commissions a rap for an event, they’re essentially asking an artist to reflect their world back to them. They’re commissioning a poet with a very modern skill set.

It pushes artists into topics they wouldn’t explore otherwise — emergency nursing, climate resilience, leadership, neuroscience. We’ve made rap videos about subjects we never would have touched without clients saying, “We need a rap about this.” It expands the art form and gives audiences something meaningful.

EP

There’s something special about hearing your own work, your own industry, turned into art. It feels personal.

BB

Exactly. People light up when they hear their experiences represented accurately. They also appreciate the craft — the speed, the musicality, the humor. It’s entertainment and communication woven together.

EP

What you’re describing feels like both a creative practice and a service model. You’re honoring the craft while giving planners something functional they can use in their event design.

BB

That’s exactly right. Event planners want attendees to feel connected, energized and seen. Rap can do that very effectively because it’s both analytical and emotional. You take all the information from a session or a keynote, filter it through rhythm and rhyme and deliver it back in a way people immediately understand — even if the topic is complex.

When people watch us write a rap during an event, they’re always surprised by how fast it comes together. What feels like magic is really a combination of training, repetition and the culture of hip hop. Rappers are used to deadlines. They’re used to improvisation. They’re used to jumping into creative challenges without hesitation.

That makes Event Rap artists uniquely prepared for the pace of a conference. Whether the client needs a freestyle, a rap-up or a custom anthem, we can meet the moment.

EP

That’s incredible. Before we wrap, is there anything you want people to think about when they consider bringing Event Rap into their program?

BB

I’d like people to think about rappers as commissionable poets. In the Renaissance, artists created masterpieces because patrons believed in their talent and gave them a clear creative challenge. When someone commissions a rap for their event, they’re doing the same thing. They’re asking an artist to speak for their community, their mission or their moment in time.

It’s good for the event because it captures the essence of what’s happening. It’s good for hip hop because it encourages artists to write about diverse topics. And it’s good for audiences because it gives them something memorable, sincere and tailored to them. Everyone wins.

EP

That’s a perfect way to close. Thank you for sharing your story and your process. This was a joy. I learned so much about how you do what you do and how much depth there is behind it.

BB

Let’s do a future episode on the evolution of Event Rap.

EP

Absolutely. I’d love that. Thank you again for being on the show.

EP

Next up is my conversation with Grammy-nominated artist Mega Ran, who brought Event Rap’s keynote performance to the Emergency Nurses Association conference in New Orleans. I watched his rehearsal and the final performance, and hearing the process behind it was fascinating. We’ll hear a clip from his set and then go straight into our interview.

EP

Mega Ran, thank you so much for joining me. I had the chance to watch you rehearse and perform at ENA, and it was incredible. How did you first get involved with Event Rap?

Mega Ran

Baba reached out to me a while back because we have similar backgrounds—we both love hip hop, but we’re also educators at heart. I was a teacher before I became a full-time musician. He told me about Event Rap and how artists could bring storytelling, lyricism and musicality to conferences. The idea appealed to me immediately because I’ve always believed rap can explain anything if you write it the right way.

EP

What was your process for creating the ENA keynote performance?

MR

It started with research. Event Rap gave me materials about emergency nursing—what the job looks like, what the challenges are, what members value. I read everything, took notes and tried to understand the emotional core of their work. Then I built an anthem around that.

Writing for an event is different from writing for an album. You’re writing for an audience that shares a purpose. They want to hear their story reflected back. My job is to translate what they do into rhythm and rhyme without losing accuracy or sincerity.

EP

You also freestyled during the event. That was one of the moments where the crowd really lit up.

MR

Freestyling at an event is fun because the audience gets to see the creation happen in real time. When you reference something that just happened — a speaker, an award, a moment — people react instantly. It feels personal, like you’re building the performance with them.

EP

When I watched you perform, I noticed how the audience responded each time you incorporated something specific from their world. It felt like the room shifted. What’s it like to create that connection on the spot?

MR

That connection is the best part. When you’re performing for a specific community — in this case, emergency nurses — you want them to feel seen. So when I mention a detail only they would know, or reference something that happened minutes earlier, they react because they recognize themselves in the lyrics. It shows them you’re not just performing atthem — you’re performing with them. That immediacy creates a bond you can’t duplicate in any other medium.

EP

You also wrote new material during the award ceremony and then performed it right after. How do you approach writing with such a quick turnaround?

MR

It’s a mix of preparation and instinct. I take notes constantly — phrases that stand out, themes that keep coming up, stories people share. While I’m listening, I’m also thinking about flow, rhythm and what kind of hook will pull everything together. When it’s time to write, I piece the notes into a verse that reflects the tone of the event.

Hip hop trains you for this. There’s a culture of speed and improvisation — someone throws you a challenge, and you deliver. That skill happens to be perfect for conferences.

EP

Your performance at ENA had both prepared pieces and spontaneous elements. How do you balance the two?

MR

The prepared anthem gives the performance structure. It’s the foundation — the part that captures the identity and mission of the group. The freestyle and the rap-up are where the spontaneity comes in. You need both.

The anthem says, “This is who we are.”

The freestyle says, “This is what’s happening right now.”

The rap-up says, “This is what we experienced together.”

That combination makes the performance feel alive.

EP

I imagine performing in a space where people might not consider themselves hip hop fans adds another layer.

MR

Definitely. A lot of people hear “rap” and think it’s not for them. But when they hear their own world reflected — their work, their challenges, their wins — it hits differently. Suddenly it’s not about genre; it’s about recognition. People who don’t normally listen to hip hop end up saying, “I didn’t expect to enjoy this, but I really connected with it.”

That’s the power of storytelling.

EP

You mentioned earlier that your background as a teacher influences the way you write. How does that show up in a performance like the one at ENA?

MR

Teaching taught me how to break things down so they’re understandable, no matter the subject. In a classroom, you take a complicated idea and present it in a way that students can absorb. Event Rap works the same way. You take an entire keynote or an entire field — in this case, emergency nursing — and translate it into something rhythmic, memorable and emotionally grounded.

My goal is always clarity. If someone in the audience walks away thinking, “He captured exactly what we do,” then I did my job.

EP

What was your favorite part of performing for the Emergency Nurses Association?

MR

It was the energy. Nurses carry so much — physically, emotionally and mentally. They deserve recognition, and they deserve to feel proud of what they do. When I performed the anthem and saw people smiling, nodding or even tearing up, it meant a lot. It showed me the work resonated.

Also, they were open. They were ready for something new. When an audience trusts you, the performance becomes a collaboration.

EP

Do you have any advice for planners who are curious about bringing an artist into their event, especially in a format people may not have experienced before?

MR

The biggest advice is: trust the process. Artists like the ones at Event Rap know how to take a theme and translate it into something powerful. Give us material, talk to us about what the group cares about and let us do the rest.

A lot of planners worry that hip hop won’t fit their audience. But the truth is, if the message is right, the medium works. When people hear themselves reflected in the story, the genre stops mattering.

EP

That’s such a good point. Before we close, what do you want people to understand about what you do?

MR

Rap is a storytelling tool. That’s what I want people to take away. It can celebrate, it can educate, it can motivate. Whether it’s an association, a corporate team or a nonprofit, every group has a story. Rap just tells that story in a different way — one that’s energetic, rhythmic and memorable.

This article appears in the November/December 2025 issue. You can subscribe to the magazine here.