Further Resources

Is Your Event Inclusive? Why Non-Alcoholic Drinks Matter Year-Round

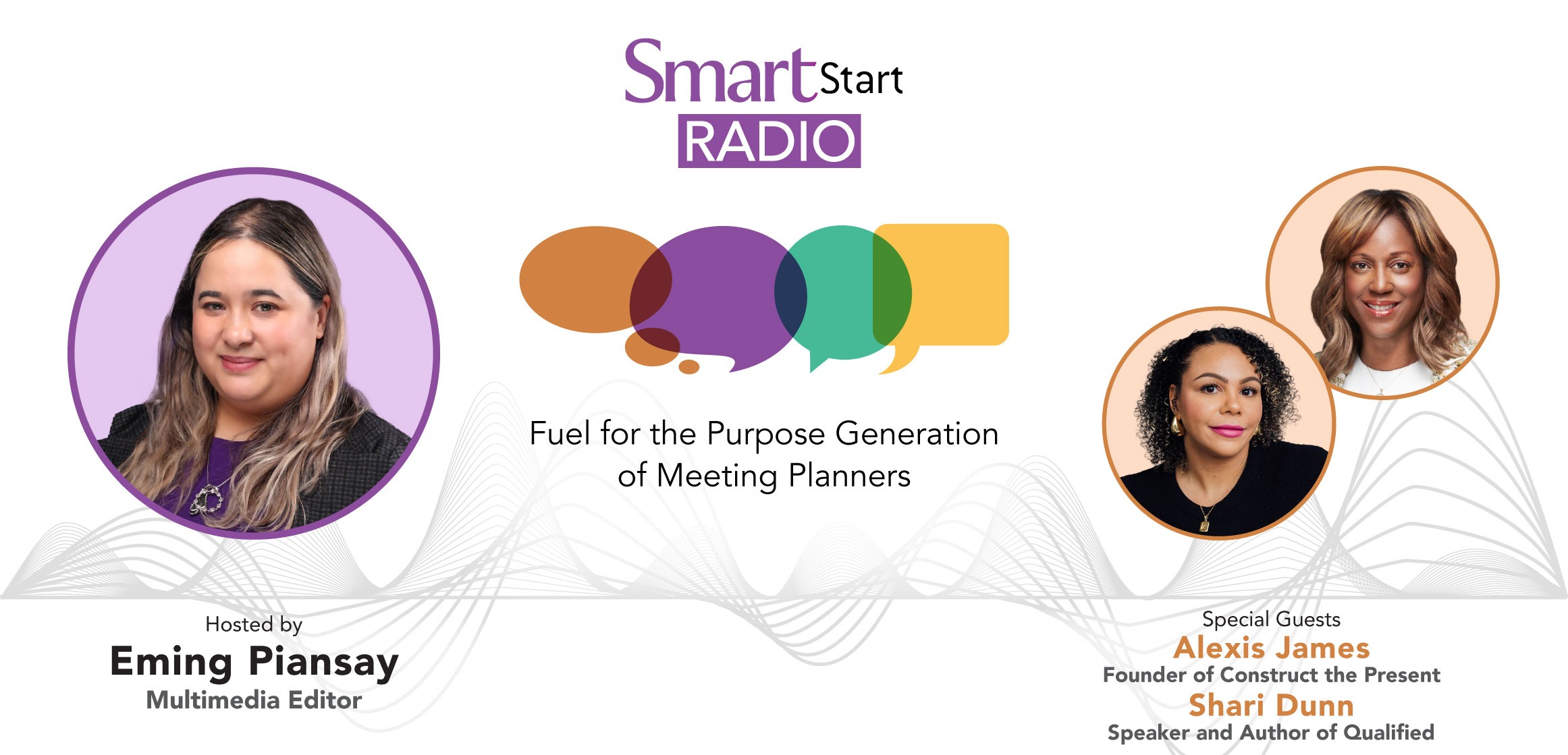

Eming Piansay

Welcome to Smart Start Radio. I’m your host, Eming Piansay, and I’m excited about this episode because there is a lot to unpack.

Late last year, I traveled to Portland for the National Coalition of Black Meeting Professionals conference. It was a meaningful experience. I met generous, thoughtful people and left feeling hopeful at a time when that can be hard to find.

DEI has become a hot-button topic across industries, especially in light of recent political and organizational shifts. While I was in Portland, I knew it was the right time to explore what inclusion looks like now.

I connected with Alexis Braly James, CEO and founder of Construct the Present, who helps organizations build healthier, more inclusive workplace cultures. I also spoke with Shari Dunn, author of Qualified: How Competency Checking and Race Collide at Work, who brings deep insight into workplace bias and leadership.

Both conversations were honest, thoughtful and timely. Let’s get started.

Alexis Braly James

For the last five years, most of my time and effort has gone into developing diversity, equity and inclusion programming through three pillars: strategic implementation, training and equity audits.

Strategic implementation is best described as fractional support. My team and I work directly with clients, often on an hourly basis, helping implement DEI practices inside organizations. We also provide training and conduct equity audits. From about 2019 to today, that has been the core of our work.

EP

If someone were to come into your office, what would your process usually look like?

ABJ

When it comes to training, we lead a three-part series because research shows it takes about 90 days and four and a half hours to change adult behavior.

We draw from a catalog of established topics, including interrupting white supremacy, acknowledging anti-Blackness, microaggressions and navigating conflict. We also develop custom trainings for organizations that want to address specific behaviors.

Because of my background in education, I have been able to design tailored programs that respond to each client’s needs.

EP

Since Smart Meetings focuses on events and meetings, how does your work fit into creating inclusive spaces for conferences and convenings?

ABJ

We have worked with conference and meeting organizers to help them create inclusive programs and environments.

One example is our work as a B Corp with B Local PDX, where we developed protocols for their annual conference. These included responsive ticket pricing, pre- and post-event surveys, and community agreements that participants commit to.

We also help organizers establish accountability processes for when those agreements are broken. It is about creating systems that support people and address harm when it happens.

EP

When did this work begin for you?

ABJ

I started in 2017. Before that, I was an educator. For a long time, this work was what people call a side hustle. I did it in the summers and after hours.

I went full time in 2019, starting with equity audits because I could do them asynchronously. Since then, I have scaled the business and expanded into different platforms.

EP

Was there a specific moment that pushed you into this work, or did it grow naturally over time?

ABJ

I am Black and biracial. My mother is white, and my father is Black. I grew up in the Portland metro area, often as the only or first Black person in many spaces.

I became very aware of justice, inequities and systems early on. I could see rules and norms that others did not always notice or name.

My parents were never married, so I moved between my mother’s predominantly white, rural family and my father’s predominantly Black, urban family. They operated in very different ways.

A simple example is birthday celebrations. With my mother’s family, everything was structured and timed. With my father’s family, it was fluid and expressive. We even sang different versions of “Happy Birthday.”

That experience helped me understand that there are many ways of showing up in the world. It sparked my interest in history, culture and systems.

EP

Since you started this work, have you seen shifts in how organizations approach DEI, especially with the recent political climate?

ABJ

Yes. There has been an intentional pushback and rollback.

I started to feel it in March. After a strong February during Black History Month, leads slowed down. Clients began pulling back services focused on diversity, equity and inclusion.

Colleagues were experiencing the same thing. Organizations were changing language, reducing programs and distancing themselves from DEI work.

I also saw large corporations removing inclusive language from their branding and policies. It affected my business and my sense of personal safety.

There were moments when I questioned whether I should change my website, remove photos or limit my visibility. Once I worked through that fear, I focused on how to support clients and adapt.

EP

How has that shift changed the way you approach your work?

ABJ

Over the last six months, I went through a process of reflection and grief. I realized that the way DEI had been practiced for years needed to evolve.

It was not always creating deep systems change, and it sometimes created tension inside organizations.

We shifted from focusing primarily on identity-based conversations to broader skill-based topics, such as navigating workplace culture, inclusive leadership and integrating technology.

We still address how identity shapes experience, but the primary focus is now on outcomes and impact.

This approach lowers defensiveness and creates space for people to engage more honestly. It also helps leaders understand how to support employees of all backgrounds.

EP

What can event planners and meeting professionals take from your work, especially as the industry continues to shift?

ABJ

One important starting point is having a clear code of conduct and a process for addressing it when it is broken.

It is one thing to say that everyone is welcome. It is another to explain how accountability and repair will happen when harm occurs.

Organizers should think through what repair looks like and how conversations will be facilitated when issues arise.

Accessibility is also critical. That includes captions, wheelchair access, seating options and visual indicators such as sunflower lanyards. These supports help people with physical and cognitive disabilities participate fully.

We also need to think about safety. Information is easily accessible online, so organizers must consider security and risk management, especially for marginalized communities.

EP

Are you concerned that the meaning of DEI could become diluted as organizations reframe their approach?

ABJ

There has always been a pendulum swing influenced by politics.

For Black communities, this work has been ongoing for generations. We do not forget the history or the struggle.

Language shifts every five or six years. That can feel disorienting, but sometimes innovation is necessary.

At the same time, we have seen real rollbacks in rights and protections, from voting access to immigration policy. That is concerning.

Last summer, I experienced a lot of sadness and worry. Now, I focus on what I can control, including my relationships, my work and my civic participation.

EP

You mentioned moving away from punishment and toward repair. What does that look like in practice?

ABJ

It depends on the organization and the situation.

Many professional associations have certification or membership standards, which makes accountability conversations easier.

Repair should move away from punishment and toward reconnection.

Instead of focusing on shame or blame, organizations should ask how someone can restore trust and contribute positively.

That process should be co-created with the people who were harmed and the person who caused harm. It may be public or private, depending on the situation.

EP

How do you respond to organizations that are concerned about return on investment when it comes to this work?

ABJ

Our work is grounded in connection.

We want people to leave training feeling connected to their purpose, their colleagues and their organization.

From a business perspective, employee retention is a major concern. It is expensive to replace staff, especially those with institutional knowledge.

People stay where they feel valued. Our work helps create that sense of value for both employees and employers.

EP

What are you hoping to see in the next five years?

ABJ

I hope people lean into in-person conversations and build relationships with those who are different from them.

I would like to see less adversarial dialogue around race, gender and sexuality.

The current climate often frames difference as a problem. I hope we move toward connection instead of division.

EP

Is there anything I did not ask you that feels important to share?

ABJ

People should visit Portland.

The best time is May through October. The food is great, and the city has a lot to offer.

Despite what some national narratives suggest, my experience living here has been positive.

EP

Thank you again to Alexis for joining me. I really enjoyed our conversation, and I encourage you to check out her work at Construct the Present. The link is in the show notes.

Now we are moving to my interview with Shari Dunn.

This was my first time recording an interview in a restaurant setting, so there is a little background noise. But I promise there are some real gems in this conversation, so stay with us.

Let’s get into it.

EP

You wrote the book Qualified. Before we dive into it, can you share a little about who you are, where you’re from and what led you to this work?

Shari Dunn

I am originally from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I come from a working-class background. My parents were union members. My father worked in a factory, and my mother worked in hospital admissions.

Being working class and being a Black woman are both central to my identity. They shape how I see the world and how I approach my work.

I went to law school and worked in several professional roles, but I have always carried that background with me. It keeps me grounded and practical.

Over time, I noticed that different standards were being applied to me and to others who looked like me. People questioned my knowledge, my leadership and my decisions in ways that did not make sense.

When I began leading a nonprofit, I saw how triggering it was for some people to see a Black woman in that role. It felt surreal, like living in an “Alice in Wonderland” world where the rules kept shifting.

EP

What made you decide that this was something you needed to write about?

SD

At first, people are confused. They notice something is wrong, but they cannot always name it.

Many people think they can outwork the problem. They believe that if they work harder, things will improve. But when the same patterns keep repeating, it becomes exhausting.

When I was running a nonprofit, I realized I was working incredibly hard and still not receiving the benefit of the doubt. I was being asked to meet standards that had not been applied to others before me.

Later, as a consultant and coach, I began hearing the same stories from clients across industries. People in health care, education, finance and nonprofit work were describing identical experiences.

They were told they were too aggressive, too focused on outcomes or not quite the right fit, even when they were highly qualified.

I realized this was not about individual failure. It was systemic.

EP

How did the book come together?

SD

I felt that people were in a lot of pain, and they did not feel safe talking about it.

They were afraid of retaliation, losing their jobs or being labeled as difficult.

I decided I was willing to take that risk and speak openly.

I wrote a proposal and shared it with a former classmate who is a novelist. He connected me with his agent, who decided to represent me.

From there, the book took shape.

I wrote it because someone had to say these things out loud. People were carrying too much alone.

EP

What response have you received since the book was published?

SD

The most common response is, “Thank you for helping me see that I’m not crazy.”

People tell me that reading the book helped them understand that their experiences were real and shared by many others.

Some have said it was healing. Others said it gave them language for things they had never been able to describe.

That sense of release is meaningful to me. It tells me the book is doing what it was meant to do.

EP

Since the book came out, have you noticed shifts in how people are responding to these issues, especially in today’s political climate?

SD

The biggest shift I see is fear.

There is a fear that has spread across workplaces and institutions. People are afraid to speak openly, even about data and documented realities.

They are worried about being bullied, targeted or fired.

I have not experienced this level of fear in my lifetime. The closest comparison I can think of is the Red Scare period in American history.

People are hesitant to talk about race, gender and inequality, even when those conversations are protected by law.

EP

Are people willing to share their experiences with you, even if they are hesitant to speak at work?

SD

Individually, yes. People are willing to talk to me.

But they are afraid to speak inside their organizations.

Institutions have become reactive and overly cautious. They are stumbling over themselves out of fear.

There has been no major court ruling prohibiting DEI discussions in private workplaces, yet many organizations behave as if there has been.

That disconnect is driven by anxiety, not by law.

EP

During your keynote, you talked about competency checking. Why does that happen so often?

SD

Competency checking happens because of how our culture treats “out groups.”

Historically, white men have been seen as the default group in professional spaces. Others are viewed as outsiders who must constantly prove themselves.

Women experienced this first. People of color, especially Black professionals, continue to experience it.

There is also a false historical narrative that questions Black intelligence and capability. That narrative still shapes unconscious behavior.

As a result, people feel entitled to ask, “How do you know that?” or “Where did you learn that?” in ways they do not with others.

EP

You mentioned that audiences often respond strongly when you talk about this.

SD

Yes. It happens everywhere.

When I describe a situation and pause, audiences complete the sentence for me. They already know what is coming because they have lived it.

I first noticed this during early readings of the manuscript. People finished my examples before I could.

That is how widespread it is.

EP

How does this connect to ideas like imposter syndrome?

SD

Imposter syndrome is often misidentified.

Many people of color and women are not suffering from self-doubt. They are responding to constant scrutiny and marginalization.

When research on imposter syndrome was first conducted, it focused on a narrow group of upper-middle-class white women. It did not reflect the experiences of marginalized communities.

If people think the problem is internal, they try to fix themselves.

If they understand the problem is systemic, they can work collectively to change conditions.

That distinction is crucial.

EP

What do you hope readers take away from Qualified when it comes to feeling confident and capable in their work?

SD

I hope people understand that many of the challenges they face are not personal failures.

They are the result of systems that have not been designed to support everyone equally.

When people misidentify structural problems as individual shortcomings, they internalize blame.

That prevents collective action.

If we recognize that many of these issues are shared, we can work together to change them.

EP

How can people who are not directly affected by these barriers become better allies?

SD

The book includes practical tools in every chapter.

After the first few chapters, each section outlines steps people can take to address inequity in real situations.

For people who are not directly impacted, the goal is awareness and intervention.

They can begin asking questions in meetings, evaluations and promotion discussions.

They can notice patterns, such as who gets opportunities and who does not.

That kind of attention matters.

EP

You’ve spoken about inequities in the speaking and consulting industry. Can you share more about that?

SD

There is not an equal playing field.

Many speakers of color are pigeonholed into narrow topics and overlooked for broader leadership conversations.

I speak on leadership, communication, career transitions and organizational strategy, not only on race.

Yet people often assume that is my only area of expertise.

I also put significant work into every keynote. I personalize my material for each audience.

I have seen other speakers repeat the same presentation in different venues and still receive higher fees and more bookings.

I cannot afford to do that. I have to bring something new every time.

EP

How do you navigate that professionally?

SD

I work with a Black woman-owned speaking agency that understands my work and advocates for me.

Having representation that believes in you is essential.

Without that support, it is much harder to gain access to opportunities.

It is not about talent alone. It is about networks and trust.

EP

You mentioned that people sometimes underestimate the work behind strong presentations.

SD

Yes. When Black professionals excel, people often describe it as “natural” or “lucky.”

They do not see the planning, strategy and discipline behind it.

That erases labor and reinforces stereotypes.

Strong communication is a skill. It is developed intentionally.

EP

What gives you hope moving forward?

SD

I am encouraged by people who are willing to listen, reflect and act.

Change is slow, but it happens through consistent, collective effort.

When people are honest about systems and committed to improvement, progress is possible.

EP

Is there anything I did not ask you that feels important for people in the meetings and events industry to hear?

SD

One thing I would add is that speakers and leaders of color are often pigeonholed.

We are frequently invited to speak only on race-related topics, even when we have expertise in many areas.

That limits opportunity and keeps conferences from benefiting from diverse perspectives.

People should think more broadly about who they invite and what voices they elevate.

EP

I want to say that your keynote and this conversation were incredibly powerful. It was emotional, thoughtful and meaningful. Thank you for sharing your story and your insight.

SD

Thank you. I appreciate the opportunity to talk about this work.

EP

Thank you again to Alexis Braly James and Shari Dunn for joining me on this episode. Their perspectives were generous, honest and deeply insightful.

I felt smarter after these conversations, and I hope you did too.

Thank you for listening to Smart Start Radio. I look forward to connecting with you again next time.